Luxury Wedding Drama, Financial Abuse, and Grandparent Rights Ultimatum: How I Protected My Assets and My Grandson

The burgundy dress hung in my closet like a bookmark in a life I wasn’t sure I still recognized.

I’d worn it for Annie’s high school graduation downtown, the hem brushing my knees as I sat in the hard folding chairs and cheered until my throat went raw. I’d worn it again for her college commencement in Bloomington, smoothing the fabric over my hips in the hotel mirror while she bounced around the room, cap crooked, laughing like the whole world had opened its arms to her. Years later, when she called to say she’d been promoted at the marketing firm off Keystone, I wore it to dinner because she’d asked me to. She’d looked me up and down, beamed, and said, “You always look so elegant, Mom.”

Now, standing in my little duplex bedroom with the mirror catching the lines time had etched around my eyes, I ran my palm over the dress and felt something unfamiliar behind my ribs.

Not excitement.

Apprehension.

The kind you feel before walking into a room where you already suspect you’ll be tested.

I leaned closer to the mirror and applied lipstick the way I’d learned to do it decades ago. A clean line, a steady hand. I’d spent most of my adult life learning to present composure even when my insides were shaking. That skill had helped me through Harold’s death, through grief so heavy it made my joints ache. It had helped me navigate hospital corridors and funeral homes and the endless paperwork that follows a life ending.

But this felt different.

This felt like being asked to defend the life Harold and I had built, not against strangers, but against my own child.

Three weeks earlier, Annie had exploded at me over the phone about her wedding.

Sixty-five thousand dollars.

That was the figure she and her fiancé, Henry, had placed on the table, not as a request or a hopeful suggestion, but as a demand. As if the careful little cushion I’d built from Harold’s life insurance, our modest brokerage account, and the paid-off home we’d sacrificed for was simply sitting there waiting to be claimed.

“Mom, you’re being selfish,” she’d snapped. Her voice had that icy edge she rarely used on me until recently. It cut in a way that made my shoulders tense even before the words fully landed. “You’re sitting on all that money while we’re trying to start our life together. Don’t you want me to be happy?”

Happy.

As if happiness required imported Italian marble for their bathroom renovation. As if joy could only exist with a luxury venue, a designer gown, a destination honeymoon in the Maldives with a private villa and an infinity pool.

I’d offered fifteen thousand. It wasn’t small. It wasn’t dismissive. It was, to me, generous enough to cover a beautiful ceremony in Indiana, a reception hall strung with lights, and a honeymoon that didn’t require a personal butler.

But Annie had stared at me like I’d offered her an insult.

“You don’t get it,” she’d said, voice low, controlled. “You never get it.”

I’d tried to explain, calmly at first, then more tightly as my own frustration rose, that money is not a bottomless well. That retirement is not a myth. That Harold had worked himself into a heart condition before he ever got to enjoy the years he’d promised himself. That I was still adjusting to living alone, still learning how to carry the shape of my days without him.

Annie had responded with silence, then a click.

And then she blocked me.

Blocked. As if I were a spam number.

For days, I stared at my phone and felt the odd humiliation of being erased by someone I’d carried in my body. Someone I’d rocked to sleep. Someone I’d stayed up with through fevers and nightmares. Someone I’d watched grow into a woman I thought I knew.

I told myself to give her time. People say awful things when they’re stressed. Weddings do that, or so the movies claim. I tried to believe it was temporary.

Then, on a Tuesday morning, while I was kneeling in the small vegetable patch behind my duplex, pulling up stubborn weeds from the damp soil, my phone chimed.

An unknown number.

I wiped my hands on my jeans and answered, expecting a telemarketer.

“Mom?”

Annie’s voice. Softer than it had been in weeks. Almost… tender.

For a moment I didn’t breathe.

“Annie,” I said, careful, like I was walking across thin ice. “Hi.”

“I’ve been thinking,” she said, and there was a fragile note under the sweetness that tugged at me in spite of everything. “Maybe we’ve both been too stubborn. Could we talk over dinner? I want to work this out.”

My heart did what it always did with my children. It leaned toward hope.

I could already feel the familiar instinct to repair, to soothe, to make things right. To apologize even if I wasn’t sure what I was apologizing for, just to stop the ache of conflict.

“I’d like that,” I said, and my voice warmed despite myself. “I’ve missed you.”

“Good,” Annie replied quickly, as if she’d been waiting for that. “Henry and I thought we’d take you somewhere nice. Franco’s on Meridian Street. You remember it, right?”

Franco’s.

The name brought back a snapshot so vivid it almost hurt: Harold across a candlelit table, his hand reaching for mine, the smell of garlic and warm bread, the soft murmur of other diners. Our twenty-fifth anniversary, back when we still talked about retirement like it was a place we’d actually get to arrive.

“Yes,” I said, swallowing. “I remember.”

“Six-thirty,” she said. “Don’t be late.”

The call ended.

I stood in my backyard with dirt under my fingernails, staring at the screen gone dark, and told myself it meant something that she reached out. That she was trying.

Still, as I finished getting ready, I couldn’t shake the way she’d said reconciliation dinner, like the phrase had been rehearsed.

I checked my reflection one last time. My hair pinned back neatly. Earrings simple. My posture straight, even though the knot in my stomach made me want to curl inward.

I grabbed my purse and paused, fingers brushing the worn photograph I kept tucked in an inner pocket: Annie and her older brother, Michael, at Disney World, both sunburned and grinning, their arms thrown around each other like the world was safe.

I took a breath, locked my door, and drove.

The route to Franco’s took me through familiar corners of Indianapolis, past neighborhoods that had once been the center of my life. The red-brick elementary school where I’d volunteered in the library. The park with the faded blue swings where I’d pushed Annie so high she’d squeal, her hair flying back, her laughter cutting through summer heat. The community center where I’d once tried to teach her to waltz before her first formal dance, my hands steadying hers while she rolled her eyes and giggled.

Each landmark felt like a page in a book turning itself.

Franco’s looked exactly as it always had: brick façade, window boxes stuffed with late-autumn mums, a warm glow behind gauzy curtains. When I opened the door, the scent of basil and garlic wrapped around me like a memory. The low hum of conversation, the clink of silverware, the faint sound of jazz drifting from hidden speakers.

Comforting.

And yet my skin prickled, as if comfort could be used as camouflage.

The hostess led me to a corner table. Candlelight flickered across white linens and polished glasses. Annie was already there, framed by the warm light, her hair in loose waves, her skin glowing in that unmistakable way some pregnant women have. She looked radiant, and the sight of her still hit me with the old, fierce love that never fully goes away, no matter what a child does.

“Mom,” she said, rising to hug me.

Her perfume was the same one she’d worn in college. For a second, my body responded before my mind could. I hugged her back, breathing her in, remembering the weight of her as a toddler asleep on my shoulder.

“You look beautiful,” I said, and I meant it. “How are you feeling? Any morning sickness?”

“Better now,” she said, touching her belly with a gesture that was both tender and oddly possessive. “Second trimester is easier, they say.”

I sat down slowly. “I’m glad you called,” I said. “I’ve missed you.”

Something flickered across her face, too quick to catch. Guilt? Calculation? It was gone before I could name it.

Before I could ask another question, Annie glanced toward the entrance. “Henry should be here any minute. He got held up at the office.”

Henry Smith.

Thirty-six. Ambitious. Smooth in conversation, the kind of man who never seemed to sweat, even in August. He worked in commercial real estate downtown, always talking about deals and markets and “opportunities.” He had a confidence that came from a life with very few real consequences.

I’d tried to like him. I really had. For Annie’s sake. But something about the way he evaluated people, the casual way he dismissed anyone he deemed less important, had always left a sour taste in me.

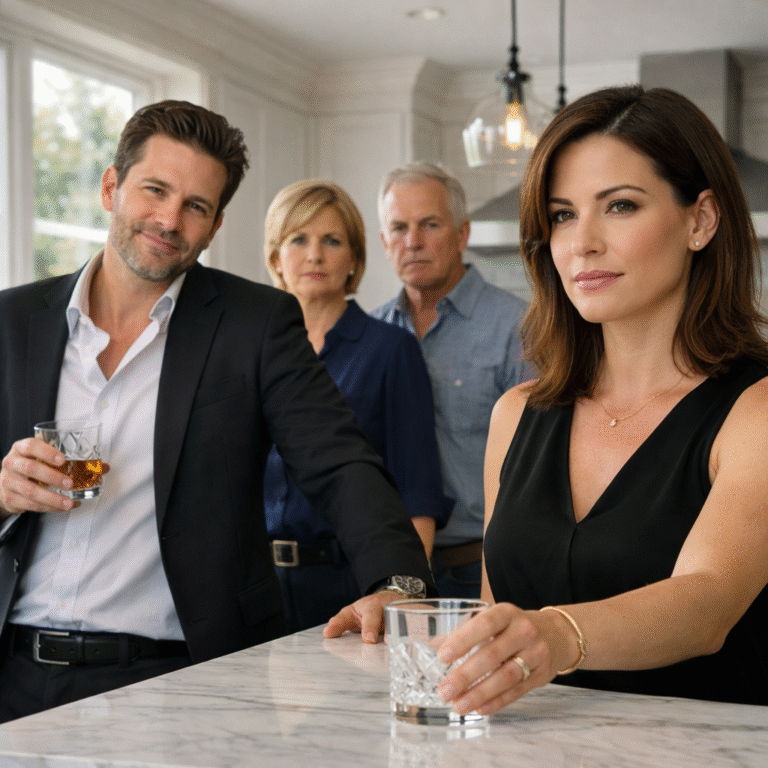

And now, sitting across from Annie in this warm restaurant, I felt the air shift when Henry arrived.

He wasn’t alone.

He walked toward our table with his too-bright smile in place, and behind him came three men in suits, each carrying a briefcase. They moved with that practiced, controlled posture I recognized from my years as a legal secretary downtown. Not family. Not friends. Professionals.

My stomach tightened so hard it felt like a fist closing.

“Mrs. McKini,” Henry said, sliding into the chair beside Annie. “Thank you for joining us.”

The three men took seats around our small table without asking, turning what should have been an intimate dinner into something else entirely. A meeting. A trap.

Annie didn’t look surprised.

That realization landed heavy.

“Annie,” I said carefully, keeping my voice level, “who are these gentlemen?”

“Mom,” she began, and her tone was too calm, too rehearsed. “These are colleagues of Henry’s. They’re here because… we thought it would be best to handle everything in one conversation.”

“Handle what?” I asked, though my body already knew the answer.

One of the men, silver-haired with a smile that didn’t reach his eyes, leaned forward. “Mrs. McKini, I’m Richard Kirk, attorney for Mr. Smith. We’ve prepared some documents we believe will be beneficial for everyone involved.”

Beneficial.

The word hung in the air like smoke.

Henry cleared his throat, slipping into that salesman voice that makes everything sound reasonable if you don’t listen too closely. “It’s really quite simple. Given your age, and the fact that you’re living alone now, it makes sense to have someone younger help manage your financial affairs. Investments, property decisions. These things can be complicated.”

“My age,” I repeated, quietly. The candlelight suddenly felt harsh. “I’m sixty-two, Henry. Not ninety-two.”

“Of course,” he said quickly, but his tone remained faintly patronizing. “But you shouldn’t have to worry about the markets and paperwork. We can take that off your plate.”

I looked at Annie. I waited for her to protest, to laugh and say this was all a misunderstanding, some misguided attempt at helping.

She sat with her hands folded in her lap, eyes fixed on the linen tablecloth like it was suddenly the most fascinating thing in the room.

Richard Kirk slid a manila folder toward me. “If you could just sign here and here, and initial there, we can have everything squared away tonight.”

My mouth went dry.

I opened the folder.

Even without my reading glasses, I could see enough: page after page of legal language, the kind designed to hide sharp teeth behind polite phrasing. But certain words stood out unmistakably.

Power of attorney.

Control.

Authority.

My house. My accounts. My investments. Everything Harold and I had built, everything I’d guarded like a small flame through grief and loneliness, handed over.

“And if I don’t sign?” I asked.

My voice surprised me with how steady it sounded. Inside, though, something cold settled into place. A stillness. A clarity.

Annie finally looked up.

Her eyes held none of the messy emotion from our argument weeks ago. No anger. No hurt. Just calculation.

“Then you won’t see your grandson grow up,” she said flatly. “It’s your choice. Henry and I talked to a lawyer. Grandparents’ rights are pretty limited in Indiana. Especially when the grandparent has shown a pattern of being… difficult.”

The restaurant noise faded into a dull hum. The jazz, the clinking plates, the murmur of other diners all blurred into something far away.

All I could hear was the blood pounding behind my ears.

My grandson.

The baby I’d been so excited about, the one I’d imagined rocking, spoiling, watching take first steps. The child I’d already loved in that abstract but powerful way you love someone you haven’t met yet because they belong to your heart by extension.

Annie was using him as leverage.

I stared at her, trying to locate the daughter I remembered. The girl who used to climb into my bed after nightmares. The teenager who cried on my shoulder after her first heartbreak. The young woman who once called me from college just to say she missed home-cooked food.

“I see,” I said quietly.

My fingers moved almost on their own. I opened my purse. Passed my wallet. Passed my reading glasses. Passed the old photo.

I took out my phone.

“Mom?” Annie’s voice wavered, the first crack in her composure. “What are you doing?”

I scrolled to the number I needed and pressed call.

It rang once.

Twice.

“Michael?” I said when my son answered, and my voice remained calm because in that moment calm was the only weapon I trusted. “It’s Mom. I need you to come to Franco’s on Meridian. Yes, now. I know you have an early shift. Just come.”

I ended the call and set the phone down beside the folder as if I’d simply placed a napkin there.

Then I looked directly at Annie.

“I think,” I said, “before anything happens, someone else wants to say a few words.”

Silence stretched across the table.

Henry’s confidence faltered. I saw it in the way his shoulders shifted, in the way his smile tightened.

The three lawyers exchanged quick looks, the kind that flicker between professionals when the script starts to go off track.

“Mom,” Annie said, reaching for that old tone she’d perfected as a teenager, the one meant to soften me, to coax me back into compliance. “There’s no need to involve Michael. This is between us.”

“Is it?” I asked, folding my hands in my lap. My fingers were steady. That surprised me. “Because when you bring three legal representatives to a reconciliation dinner, you’ve already involved quite a few people.”

Richard Kirk cleared his throat. “Mrs. McKini, perhaps we should discuss this more privately. Family matters can be… emotional.”

I met his gaze. “How thoughtful of you to notice.”

Henry leaned forward, trying again, voice warm and coaxing. “Look, Mrs. McKini… may I call you Margaret? We’re going to be family soon.”

“You may call me Mrs. McKini,” I replied.

His smile twitched. “Of course. Mrs. McKini. I think there’s been a misunderstanding. We’re not trying to take anything from you. We just want to maximize your returns. Make sure you’re positioned well for retirement, and that Annie and the baby are secure.”

“The baby,” I repeated, and I turned to Annie. “When did you start planning this? Before or after you called me about reconciliation?”

Her chin lifted, stubbornness flashing. Harold’s stubbornness, but sharpened into something colder. “Does it matter?”

“It matters to me.”

“Fine,” Annie snapped, loud enough that a couple nearby paused. “We’ve been discussing options for weeks. Ever since you made it clear you don’t care about my happiness or my future.”

“Options,” I echoed softly. “Not threats. Not pressure. Not an ultimatum with lawyers.”

“It’s not extortion,” Annie insisted, voice rising. “It’s family. It’s what families do for each other.”

“What families do,” I said, my tone quiet but firm, “is support each other without ambushes.”

The youngest attorney, the one with nervous energy and expensive cologne, leaned forward as if he couldn’t wait to demonstrate his usefulness. “Mrs. McKini, if I may, grandparents’ rights in this state are quite limited. If your daughter chooses to restrict access, your legal recourse is…”

“Excuse me.”

The voice came from behind me, warm and familiar, and it hit my spine like relief.

Michael stood at the edge of the table in dark blue hospital scrubs, his badge clipped at his pocket. His hair was slightly mussed, like he’d run a hand through it all the way from the parking garage. At thirty-seven, he had Harold’s steady presence and my mother’s sharp eyes.

“I’m Dr. Johnson,” he said to the table generally, but his gaze landed on Henry like a scalpel. “I believe you called me, Mom.”

“I did,” I said, gesturing to the empty chair. The hostess appeared quickly with one, sensing the tension without understanding it.

Michael sat, his eyes sweeping the table, taking in the suited men, the folder, Annie’s rigid posture, Henry’s forced smile. As an ER physician, he’d walked into chaos for a living and learned to identify the real threat within seconds.

“Colleagues,” Michael repeated mildly. “I see. And they are?”

Henry rose, extending his hand. “Henry Smith. Annie’s fiancé. These are business associates. We were just discussing financial planning with your mother.”

Michael shook Henry’s hand briefly, then released it. “Financial planning. At Franco’s. On a Tuesday night. With my sister three months pregnant.”

He turned to Annie, voice softer but still edged. “How are you feeling, by the way? Any complications?”

“I’m fine,” Annie said, but her voice had shrunk. The certainty drained.

“Good,” Michael replied.

Then he picked up the folder, flipped it open, and scanned the first page.

“Power of attorney,” he murmured.

He closed it and set it aside like it was something dirty.

“Mom,” he asked, looking at me now, “did you request help managing your finances?”

“I did not,” I said.

Michael turned back toward the table. “Then we’re done.”

Henry’s smile tightened. “Now wait, just a minute…”

Michael’s voice went flat, clinical. The tone he used when someone in Trauma Bay Two needed to be escorted out. “I’m not asking. Would you all mind giving me a few minutes alone with my mother?”

The lawyers hesitated. Henry looked to Annie for direction, but Annie’s eyes were down again, fixed on her hands.

Richard Kirk finally nodded stiffly. “We’ll be right over there,” he said, motioning toward the bar. “Mrs. McKini, please don’t make any hasty decisions.”

The four of them moved away, though their attention stayed locked on our table like a tether.

Michael leaned forward, voice low. “Mom. Talk to me.”

For the first time that evening, I felt tears press behind my eyes, not out of fear, but out of the sudden relief of being seen as a person instead of a bank account.

“They want me to sign everything over,” I whispered. “If I don’t, Annie says I won’t see my grandson.”

Michael was quiet for a long moment. His fingers drummed lightly on the table in a rhythm I recognized from his teenage years, the tell that he was thinking hard.

“How much did they ask you for originally?” he asked. “For the wedding.”

“Sixty-five thousand,” I said.

Michael let out a low whistle, disbelief and anger mixing. “And you offered fifteen.”

“Yes.”

“Mom,” he said, eyes narrowing, “are you having any problems? Memory issues, confusion, anything that would make them think you need help managing your affairs?”

A humorless laugh almost escaped me. “Last month I balanced my checkbook to the penny. I renegotiated my car insurance and saved two hundred dollars a year. I caught an error in my property tax assessment that saved me eight hundred. Does that sound like someone who can’t handle her own business?”

“No,” Michael said, jaw tightening. “It sounds like the woman who taught me how to manage money well enough to make it through med school without drowning.”

I swallowed hard. “You worked for that.”

“I worked for it because you taught me how,” he replied.

His gaze flicked toward Annie at the bar, where Henry was gesturing sharply, his free hand slicing the air, already recalculating.

“What happened to her?” Michael asked quietly. “When did she become this person?”

I stared at my daughter’s profile, her posture rigid, her hand resting protectively on her belly as if shielding the baby from the consequences of her own choices.

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “Maybe I protected her too much. Or maybe Henry saw an opening. But she’s thirty-four. She made her choices.”

Michael exhaled slowly. “What do you want to do?”

Before I could answer, Henry marched back to the table, lawyers trailing behind. Annie followed, slower, her face tight and pale.

“I’m sorry to interrupt,” Henry said, not sorry at all. “But we do have a timeline. The wedding is in three months. Deposits are due. Vendors need commitments.”

“Of course,” I said, and I stood.

The candlelight flickered. The air smelled of garlic and bread. Nearby, a couple laughed over a shared plate of pasta, unaware their evening was taking place in a different world than ours.

I straightened my shoulders and felt something settle in me. That hard, still clarity again.

“I’ve made my decision,” I said, loud enough for everyone to hear.

Annie went very still.

Henry’s face brightened, relief rushing in like he couldn’t stop it.

“I’ll sign,” I said.

Henry’s smile widened. One of the lawyers actually looked pleased, like a fisherman seeing the line tighten.

Annie’s shoulders sagged, a fraction of tension releasing.

Then I added, “But before anything happens, someone wants to say a few words.”

I reached into my purse again. My fingers wrapped around my phone. I scrolled to a number I’d been smart enough to save weeks ago, the day Annie first threatened me with my grandchild.

“Louise?” I said when the call connected. “It’s Margaret McKini. Could you come to Franco’s on Meridian? And bring the documents we discussed.”

Henry’s relief froze. “Who is Louise?” he demanded.

I ended the call, placed the phone gently on the table, and looked at him with the calm of a woman who had finally stopped being shocked by what her child could do and started being prepared.

“Louise Qualls,” I said pleasantly. “My attorney.”

The silence that followed had teeth.

Richard Kirk’s predatory smile vanished. The youngest lawyer shifted in his chair like his suit collar had suddenly tightened.

Henry blinked rapidly. “When did you hire an attorney?”

I held his gaze. “The same day you started asking my neighbors about my mental state.”

Annie went pale. “Mom, we never…”

“Never what, sweetheart?” I asked, still polite. “Never had Henry stop by my cul-de-sac to ask if I’d been acting strangely? Forgetting things? Paying bills on time? Did you really think Mrs. Anderson wouldn’t mention that a nice young man had questions about whether I seemed confused?”

Michael’s head snapped toward Annie, understanding dawning. “Jesus, Annie,” he said softly. “How long has this been going on?”

Annie’s mouth opened. Closed. Her eyes flicked to Henry.

I reached into my purse and pulled out a small envelope.

Then I slid its contents onto the table.

Photos of my house taken from different angles, printed. Notes. A few emails I’d gotten through Louise that showed Henry’s inquiries and a private investigator’s brief summary of my routines.

The lawyers’ faces shifted as they scanned the evidence. Discomfort replaced confidence.

“It’s amazing,” I said, voice still even, “what people will tell a sweet-faced older woman who asks the right questions. Especially when they assume she’s harmless.”

The youngest lawyer began to sweat.

“Mrs. McKini,” he stammered, “I think there may have been some misunderstanding about our client’s intentions…”

“Oh, I understand their intentions,” I replied. “The question is whether you understood what you were being asked to participate in.”

Annie’s eyes filled with tears, but they did nothing for me anymore. Not because I’d stopped loving her, but because I’d stopped confusing tears with accountability.

The candle flame flickered, and for a moment I watched its tiny dance and thought of Harold. How he would have hated this. How he would have sat beside me with his steady hand on my knee, his presence a quiet shield.

Instead, I had Michael. And I had myself.

And in a few minutes, I would have Louise.

For the first time since Annie had made money the centerpiece of our relationship, I felt something like certainty.

They had brought paperwork and threats.

I had brought preparation.

And I wasn’t done yet.

The air at our table changed after I said the words my attorney.

It was subtle at first, like the moment right before a summer storm breaks, when the birds stop singing and the heat goes strange. Henry’s grin had nowhere to go, so it collapsed into a hard line. Richard Kirk’s posture stiffened, the predatory ease gone from his shoulders. Even Annie looked shaken, her hands tightening on the edge of the table as if she needed something solid to hold onto.

Michael sat back, eyes moving between them with the calm precision of a man who spends his days walking into emergencies and refusing to panic.

“You hired an attorney,” Henry said again, slower, as if repeating it might change the fact.

“I hired an attorney,” I agreed. My voice stayed even. I didn’t give him anger to bite into. I didn’t give him tears to play with. “Because you don’t bring legal paperwork to a family dinner unless you plan to use it.”

Richard Kirk tried to recover, smoothing his expression. “Mrs. McKini, there’s no need to escalate. We can all take a breath here.”

“Escalate,” I repeated, almost amused. “You brought three legal representatives and a power of attorney packet to an Italian restaurant. You threatened me with my grandchild. If that isn’t escalation, I’d hate to see what you call it.”

Annie’s face pinched, and for a second I saw a flash of something beneath her composure. Shame, maybe. Or anger that I wasn’t folding.

“Mom,” she said, voice thin, “why are you doing this here?”

I looked at her, really looked. The candlelight caught the curve of her cheek, the glossy sheen of her lipstick. She looked beautiful and exhausted, pregnant and self-contained, like a woman playing a role she couldn’t fully inhabit.

“Because you did this here,” I said quietly. “You called it reconciliation. You chose the restaurant. You brought the paperwork. You set the stage.”

Henry’s jaw worked. “This isn’t necessary. We can solve this without outside interference.”

Michael’s voice cut through, low and cold. “Outside interference? You mean the person my mother hired to protect herself from you?”

Henry snapped his gaze to Michael. “This is between your mother and your sister.”

Michael didn’t blink. “You made it between all of us when you tried to take control of her finances.”

Richard Kirk shifted in his chair, eyeing the envelope of printed proof on the table like it might bite him. “We don’t have to discuss those… materials,” he said carefully. “Our intent was to ensure Mrs. McKini has support.”

“The kind of support that signs her life over,” I murmured.

The youngest attorney, who had been eager a moment ago, now looked like he wished he could melt into the booth. He kept flicking glances toward the exit.

Annie inhaled sharply, then exhaled. “Mom, you’re acting like we’re criminals.”

I felt something inside me tighten, not with rage, but with sorrow so clean it stung.

“No,” I said. “I’m acting like a woman who understands that love doesn’t come with contracts and threats.”

A long silence stretched. In the distance, someone laughed loudly at the bar, unaware of the quiet violence happening at our corner table. A server passed with a tray of steaming plates, the scent of marinara and garlic floating through the air.

Henry leaned forward again, attempting warmth. “Margaret, we’re just trying to help. You’ve been alone since Harold passed. You’ve been vulnerable. We thought… well, we thought it would be comforting for you to know Annie and I can handle the bigger decisions.”

There it was. The story he wanted to tell.

Vulnerable widow. Confused older woman. Helpful young couple stepping in.

He said it with enough softness that a stranger might have believed him.

But I knew what comfort looked like. Harold had comforted me with quiet presence. Michael comforted me by showing up in scrubs without hesitation. Comfort wasn’t a stack of papers and three suited men at a table.

“Do you want to know something about being alone?” I asked Henry.

He hesitated. “Of course.”

“I’m alone because my husband died,” I said, and my voice stayed calm even as the grief flashed hot for a second behind my ribs. “Not because I became incapable. Not because I became foolish. I paid the bills while Harold was alive. I handled our insurance. I kept us steady when his health declined. I didn’t suddenly lose my mind because I lost my partner.”

Annie flinched, and for a moment I thought she might speak, might interrupt, might finally say something human.

Instead she stayed silent.

The candle flame shivered.

I checked my phone without picking it up, the way you check a clock in your mind. Louise would be on her way. She always was. She’d been my attorney for years, the kind of woman who didn’t just understand the law, but understood people who thought law could be used like a weapon.

Henry watched my face, trying to read it. His eyes narrowed, suspicion replacing charm.

Richard Kirk spoke again, smooth but cautious. “Mrs. McKini, perhaps it’s best if we reschedule. Bring everyone’s counsel. Have the conversation in an appropriate setting.”

“And by appropriate you mean your office,” I said.

He didn’t deny it.

Annie finally lifted her chin. “Mom,” she said, voice controlled, “I’m not doing this to hurt you. I’m doing this because I’m scared.”

The words landed, and for a second, I felt the familiar pull toward her. The maternal reflex. The urge to step closer and soothe.

But then she continued.

“I’m going to have a baby,” she said. “Henry and I need security. We need to know we’re going to be okay. You have resources, and you’re acting like you can’t help.”

“You’re not asking for help,” I said softly. “You’re asking for control.”

“It’s not control,” Annie insisted. “It’s partnership.”

Michael’s laugh was short, sharp. “Partnership doesn’t start with threats, Annie.”

Henry’s hand slid over Annie’s knee under the table, a gesture that looked protective but felt possessive in the way he held it there, anchoring her.

“Please,” Henry said, voice tightening, “let’s be rational. We are family. And we can all agree this is best for the baby.”

The baby.

As if invoking that word would make everyone surrender.

My phone buzzed softly.

A text from Louise: Parking. Be there in two.

I didn’t look at Henry. I didn’t look at Annie. I simply set my phone down again and waited.

Two minutes is a long time when people are trying to force an outcome. Henry shifted like a man calculating alternate routes. Richard Kirk whispered something to the other attorneys. Annie stared at the tablecloth as if she could erase the last thirty minutes by focusing hard enough.

Michael sat still, a quiet wall beside me.

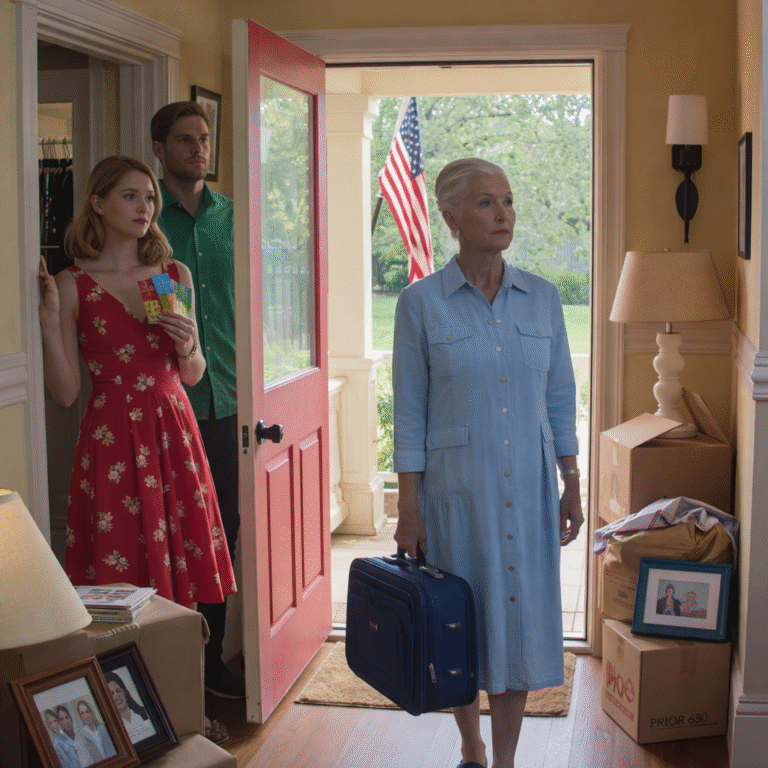

Then I saw her.

Louise Qualls entered Franco’s with the purposeful stride of a woman who had been underestimated her entire life and had made a career out of proving people wrong. She was small, silver-haired, dressed neatly, and carried a canvas tote bag over one shoulder like a badge of ordinary decency. Her eyes were clear and sharp, the kind that miss nothing.

She spotted me immediately.

“Margaret,” she said, warm, and the way she said my name felt like a hand closing around mine. “I got your call.”

“Louise,” I replied. “Thank you.”

She moved to our table without hesitation, and the four people across from us stiffened as if the temperature had dropped.

Louise glanced around the table, taking in the lawyers, the folder, the posture of predation. She did it with the same calm interest a surgeon might have while examining a stubborn growth.

“Gentlemen,” she said pleasantly. “I understand you have documents you’d like my client to sign.”

Richard Kirk rose slightly, adjusting his tie. “Ms. Qualls, this is a family matter.”

“Qualls, Peterson & Associates,” Louise corrected mildly. She set her tote bag on the bench beside her and slid into the chair Michael pulled out. “And yes, it is. That’s why I’m here. Family relationships are often the easiest place for financial exploitation to hide.”

Henry bristled. “Exploitation is a strong word.”

Louise turned her head toward him, her smile polite but empty. “Then stop behaving in ways that invite it.”

The silence that followed was thick. Even the restaurant’s background noise seemed to dim, as if the room had leaned in.

Louise opened her bag, pulled out a neat stack of papers, and laid them on the table with the same precision I’d once watched Harold use when he leveled a picture frame. Orderly. Final.

“Before we discuss any power of attorney,” she said, “you should see what Margaret has already put in place.”

Henry leaned forward, eyes flicking down to the top page.

His face changed as he read.

Annie reached across to see over his shoulder, her breath catching.

Richard Kirk’s eyes narrowed.

“Irrevocable trust,” Louise said conversationally, like she was discussing the weather. “Established two weeks ago. Margaret’s house, her investment accounts, her life insurance proceeds. All transferred into the McKini Family Trust.”

Annie’s mouth parted. “The trust,” she said slowly, reading. “It says the beneficiaries are… your children.”

“Both born and unborn,” I said quietly, finishing the sentence that made Henry’s throat bob. “With Michael as trustee until they reach twenty-five.”

Henry’s hands tightened on the paper.

The air around him shifted, the way it does when a man realizes the room is no longer his.

“That’s… that’s not what we discussed,” Annie whispered, voice shaking.

“We didn’t discuss this,” I corrected gently. “You told me what you wanted. You threatened me. You tried to corner me. So I protected what Harold and I built in a way you can’t override with dinner and paperwork.”

Louise tapped the documents lightly. “The trust is structured for education, healthcare, and reasonable living support for the beneficiaries. There is no provision for third-party control.”

Henry’s voice sharpened. “What about the wedding? We have deposits. We have plans.”

Louise looked at him as if she’d just noticed a stain on her sleeve. “I don’t see how an Italian-marble bathroom renovation qualifies as a beneficiary’s need.”

Annie’s eyes flashed. “That’s not fair.”

Michael’s voice was steady. “What’s not fair is using your baby as a bargaining chip to take Mom’s assets.”

Annie’s breath hitched. Tears sprang up in her eyes, and for a moment I saw the daughter I remembered, the one who cried when her hamster died, the one who clung to me the first day of kindergarten.

But then she looked at Henry, and that hard set returned to her jaw.

“We had an agreement,” Henry said, leaning toward me, anger slipping through the veneer. “You said you’d sign.”

“I said I’d sign,” I replied calmly, “and then I said someone wanted to say a few words.”

Louise smiled, the kind of smile that had likely made more than one bully sweat. “And I did.”

Richard Kirk cleared his throat, posture suddenly cautious. “I think we may have been operating under misunderstandings about Mrs. McKini’s intentions.”

“Which intentions?” Louise asked. “Her intention to remain competent? Her intention to protect herself from coercion? Or her intention to ensure her grandchildren benefit without predatory access?”

Kirk didn’t answer.

The youngest attorney stared at the trust paperwork as if it had transformed into a snake.

Henry’s cheeks flushed. “You can’t just cut Annie out.”

“I didn’t cut her out,” I said softly. “I cut you out.”

Annie looked at me like I’d slapped her, and my chest tightened because no matter what she’d done, it still hurt to hurt her. Motherhood doesn’t switch off cleanly.

“You don’t even know what you’re doing,” Annie said, voice trembling. “You’re punishing me. You’re punishing your own daughter.”

“I’m protecting my legacy,” I replied. “And I’m protecting your child’s future from becoming collateral in whatever game you and Henry are playing.”

Henry leaned back, scanning the table, eyes darting like he was searching for a crack he could wedge open.

Louise’s voice stayed calm. “Mr. Smith, you may want to consult separate counsel about the implications of your efforts to establish incompetency narratives. It can be interpreted unfavorably in certain contexts.”

The threat was polite. But it landed.

Richard Kirk began sliding papers back into his briefcase, his movements suddenly brisk.

“I think,” he said carefully, “it would be prudent for all parties to pause any signing tonight.”

“Excellent idea,” Louise replied. “Margaret, shall we go?”

Annie’s tears fell now, quiet and careful. Her hands fluttered briefly toward her belly as if to remind us again of the baby, of the leverage.

“Mom,” she whispered, and in her voice I heard something that might have been real fear, or might have been desperation for control. “Don’t do this. Please.”

I stood.

The candlelight wavered, throwing soft shadows across her face.

“I’m already doing it,” I said gently. “And I’m not doing it to punish you. I’m doing it because you gave me no choice.”

“Choice,” Annie echoed, bitter. “You always make it sound like I’m the villain.”

Michael rose too, placing himself slightly between Henry and me without making it obvious. “You brought lawyers to a dinner, Annie. You threatened Mom with her grandchild. You don’t get to call yourself innocent.”

Louise gathered her papers with smooth efficiency.

I looked at Annie, really looked, and felt the grief again. A clean slice.

“When you’re ready to have a real conversation,” I said quietly, “about your baby, about your life, about what you tried to do tonight, call me. But call me alone.”

Then I turned my gaze to Henry.

His face was rigid with contained fury, his eyes still calculating.

“As for you,” I said, voice calm, “stay away from my home. Stay away from my accounts. If I hear you’ve made one more inquiry into my competency or finances, Louise and I will have a very different conversation.”

Henry’s lips parted like he wanted to argue, but the attorneys had already begun their retreat. A man like Henry hates being seen beside a losing position.

Michael pulled out his wallet and dropped cash on the table to cover the drinks and appetizers we hadn’t touched. It was such a simple, practical gesture. It reminded me of Harold, the way Harold always insisted on paying even when he was furious, as if saying, I won’t let you claim we wronged you.

“Annie,” Michael said, voice softer now, “you’re welcome at my place if you need somewhere to think. But you come alone. No financial schemes. No pressure.”

Annie didn’t answer. She just sat there crying while Henry’s hand clamped down on her shoulder, firm, steering, as if he could hold her in place.

We walked out into the crisp Indiana night.

The restaurant’s warm glow spilled onto the sidewalk behind us. The air smelled like cold leaves and car exhaust. A nearby flag snapped softly in the breeze.

My lungs filled with cold, and for the first time in weeks, it felt like a real breath.

Louise walked beside me, her steps steady. “How do you feel?” she asked.

I thought of Annie still inside, pregnant and furious, tangled up with a man who had treated my life like an account to be accessed. I thought of Harold, and how proud he would have been that I didn’t fold. I thought of my grandson, the baby I hadn’t met yet, already being used as a lever.

“Free,” I said, and my voice surprised me with its certainty. “For the first time in months, I feel free.”

Louise nodded, as if she’d been waiting to hear that. “Good,” she said. “Now comes the hard part.”

“What’s that?”

“Living your freedom,” she said. “Not just defending it.”

In the car ride home, Michael drove behind us to make sure we got there safely, as if I were the one at risk on the road. The gesture warmed me more than I could say.

When I stepped into my duplex, the familiar scent of home wrapped around me. Clean laundry. Coffee lingering in the air. The faint smell of soil from my little garden.

I set my purse on the table and stood still for a long moment, listening to the quiet.

No buzzing phones. No legal voices. No threats.

Just my own breathing.

Three weeks later, the quiet held.

It wasn’t empty. It was peaceful, and I was learning there was a difference.

Morning sunlight painted geometric patterns across my kitchen floor. I stood at the counter making coffee for two because Janet Waters was coming over, and I’d come to appreciate a woman who showed up with food and honesty instead of opinions and pressure.

Janet had moved into the other half of the duplex not long after Harold’s death, a widow like me, though she carried her grief with a briskness that made it look almost like competence. She was sixty-seven, silver hair cut in a practical bob, blue eyes sharp and kind. She had an immunity to drama that I admired, and a talent for telling the truth without cruelty.

Right on time, the doorbell rang.

I opened the door to find Janet holding a covered casserole dish and wearing a look that told me she had something to share.

“I brought my grandmother’s cornbread,” she said, stepping inside and shrugging off her denim jacket. “And I heard something interesting at the bank yesterday.”

I poured her coffee into one of my mismatched mugs, the kind you collect when you stop trying to impress anyone.

“What kind of interesting?” I asked.

Janet’s mouth tilted into a small, satisfied smile. “Henry Smith was at the bank. People talk, you know. Apparently some of his business accounts are under review. His partner noticed irregularities. Client deposits being used for personal expenses. Word is he’s having… professional difficulties.”

I sat down slowly, letting the information settle.

I didn’t feel triumph.

I felt something quieter.

Confirmation.

Men like Henry move through life believing consequences are for other people. When consequences finally arrive, it’s rarely dramatic. It’s paperwork. It’s a phone call. It’s a door closing softly and firmly.

“And Annie?” I asked, though I wasn’t sure I wanted the answer.

Janet snorted softly. “I saw her last week. Shopping for wedding dresses at an outlet in Greenwood. Looked like she wanted to be seen looking like she didn’t care.”

I stared into my coffee and watched the surface ripple as my hand trembled slightly. Not from fear, but from the strange mixture of grief and vindication that comes when you realize your child is learning life the hard way.

Janet set her mug down and studied me. “You okay?”

I nodded. “I’m not sure.”

“That’s honest,” she said. “It’s also allowed.”

Later that morning, my phone rang. A local number I didn’t recognize.

I hesitated, then answered. “Hello?”

“Mrs. McKini?” a young woman asked. “My name is Diana Reed. I’m calling from the Meridian Community Center.”

I glanced at the magnet on my fridge with the center’s logo, the little printed American flag in the corner.

“Yes,” I said cautiously. “How can I help you?”

“Louise Qualls mentioned you,” Diana said. “We run a program for seniors dealing with financial exploitation. By family, caregivers, people they trust. Louise thought you might be interested in volunteering.”

The words hit me in a way I didn’t expect. Financial exploitation. Seniors. Family.

The phrase made my skin prickle, not because it felt shameful, but because it named what had happened with clean clarity.

Diana explained the program for a while, her voice steady and professional. Peer support. Education. Helping people recognize manipulation. Connecting them with resources.

As she spoke, I looked around my kitchen. The small table where I’d eaten alone after Harold died. The counter where I’d stood shaking after Annie blocked me. The place where I’d stared at the ceiling at night wondering if I was losing my daughter.

Somehow, the thought of turning this into something useful felt like oxygen.

When I hung up, Janet was watching me.

“You’re going to do it,” she said.

It wasn’t a question.

“I think I am,” I admitted.

Janet nodded, pleased. “Good. You need something that’s yours.”

That afternoon, Michael called.

His voice sounded tired in the way it always did after a long hospital shift, but there was a tightness underneath that told me the call wasn’t just to check in.

“Mom,” he said, “heads up. Annie’s been asking about the trust.”

My stomach tightened, but not with panic this time. With readiness.

“What about it?” I asked.

“She asked if there’s any way to challenge it,” Michael said. “She used the phrase undue influence. Like Louise pressured you into decisions you wouldn’t have made.”

I let out a slow breath. “That sounds like Henry’s wording.”

“Probably,” Michael agreed. “But Annie’s the one making the calls. She also asked if I think you’d change your mind if she broke off the engagement.”

The question sat between us for a beat.

“What did you tell her?” I asked.

“I told her decisions motivated by money rarely lead to happiness,” Michael said. “And that if she wants to fix things with you, it starts with honesty.”

“And then?”

“She hung up on me.”

I closed my eyes briefly, feeling the familiar grief, then the familiar steadiness behind it.

“Michael,” I said, voice soft, “whatever happens with Annie doesn’t change anything between us. You’re a good man. I’m proud of you.”

Michael’s exhale was audible through the phone. “I keep thinking I should be able to fix it,” he admitted. “Find some middle ground.”

“Some things can’t be fixed,” I said. “Some things have to be faced.”

When I ended the call, the house felt quiet again.

Not the lonely kind.

The kind that makes room for a person to hear herself think.

And for the first time in a long time, I didn’t feel like I was waiting to be ambushed.

I felt like I was building something they couldn’t take.

The weeks that followed settled into a quiet I hadn’t known I was capable of living inside.

Not the hollow quiet that echoes, not the kind that reminds you of what’s missing, but a steady, breathable silence. The kind that lets you hear your own thoughts without flinching. The kind that doesn’t demand explanations.

I woke up each morning and made coffee for myself without rushing. I tended my small garden out back, kneeling in the dirt and feeling grounded in a way I hadn’t since Harold was alive. I reorganized a closet that had been ignored for years. I reread old books. I let the days arrive and leave without bracing for impact.

The phone stayed mostly quiet.

No more legal voices. No more carefully worded threats. No more “concerned” messages disguised as pressure.

For the first time in months, I wasn’t waiting for something bad to happen.

Janet became part of my daily rhythm without either of us announcing it. She knocked in the mornings with leftovers or questions or observations about the neighborhood. Sometimes we sat at the table with coffee and talked about nothing in particular. Sometimes we talked about everything.

One morning she set her mug down and said, “You know, most people would have folded.”

“I almost did,” I admitted.

“But you didn’t.”

“No,” I said. “I finally realized that folding would have cost me more than standing ever could.”

She smiled at that, satisfied.

The volunteer work at the community center began quietly. No big announcements. No speeches. Just folding chairs arranged in a circle, a pot of coffee, a box of tissues placed deliberately within reach.

The first night I sat among strangers and said, “My name is Margaret, and my daughter tried to take control of my finances by threatening to keep my grandchild from me,” my voice didn’t shake.

Some people cried. Some nodded. Some stared at the floor, recognition heavy in their eyes.

Each week after that, the room filled with stories that sounded different on the surface but carried the same bones underneath. Adult children who felt entitled. Caregivers who confused access with ownership. Relatives who used love as leverage.

I didn’t fix anyone. I didn’t try.

I listened. I shared. I showed them where the exits were.

Michael came once a month to speak to the group, straight from the hospital, still wearing his badge. He talked about guilt. About grief. About how caring doesn’t mean surrendering yourself piece by piece.

Watching him stand there, steady and compassionate, I felt something I hadn’t allowed myself to feel in a long time.

Pride without fear.

Annie stayed silent.

No calls. No texts. No messages through mutual acquaintances. Just a vacuum where she used to be.

I told myself not to check her social media. I mostly succeeded.

Then one afternoon Janet came in from the mailbox holding an envelope and said carefully, “This one’s for you.”

There was no return address, but I recognized Annie’s handwriting immediately. The loops tighter than they used to be. Less flourish. More control.

I didn’t open it right away. I set it on the table and let it sit there while I finished making soup. While I wiped down the counter. While I reminded myself that whatever was inside could not undo what I’d already done.

When I finally opened it, there were only three sentences.

She had the baby.

A girl.

They named her Eleanor.

I sat down slowly.

Eleanor.

My mother’s name.

It landed like both a bridge and a test.

Janet watched me carefully. “Do you want to go to the hospital?”

I shook my head, the answer clear before the question finished. “Not yet.”

The phone rang that evening.

It was Michael.

“Mom,” he said gently, “Annie asked me to call you.”

I closed my eyes. “About the baby.”

“Yes.”

“And?”

“She wants you to visit. She said… she said she knows things got out of hand.”

Out of hand.

Not wrong. Not cruel. Not manipulative.

Just inconvenient.

I thought of the trust documents. Of the photos on the table at Franco’s. Of Henry’s hand on her knee. Of the way she’d said my grandson like it was a bargaining chip.

“I want to meet my granddaughter,” I said slowly. “But not like that.”

Michael didn’t interrupt.

“I won’t be rushed. I won’t be cornered. And I won’t pretend nothing happened.”

“What do you want?” he asked.

I took a breath and felt how solid the answer was.

“I want boundaries. Supervised visits. No discussions about money. No negotiations. No guilt.”

“I’ll tell her,” Michael said.

Two days later, Annie responded.

Not with anger. Not with apologies.

With conditions.

She wanted a fresh start. She wanted us to move forward. She wanted me to “focus on the baby and let the past go.”

She did not mention the lawyers.

She did not mention the threats.

She did not mention Henry’s behavior.

I read the message twice and felt something settle into place.

I wrote back.

Not a paragraph. Not a debate.

Just this:

I would love to meet Eleanor.

I will do so with Michael present.

If my boundaries cannot be respected, I will leave.

She didn’t reply right away.

That told me everything.

The meeting happened a week later.

Michael drove. Annie chose a neutral place, a small sitting room at her apartment complex. Henry was “out,” which I noted without comment.

When Annie opened the door, she looked thinner. Tired. Older in a way pregnancy sometimes does to people who haven’t rested inside themselves in a long time.

The baby was asleep in her arms.

For a moment, all the tension in the room paused.

Eleanor had Annie’s dark hair and Harold’s nose. Her tiny chest rose and fell with the seriousness of newborn sleep. One fist rested against her cheek like she was already guarding her dreams.

I sat down slowly.

“May I?” I asked.

Annie hesitated, then handed her to me.

The weight of that child settled into my arms like something ancient and familiar. Warm. Solid. Real.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t gush. I didn’t promise anything.

I just held her.

Annie watched me closely, like she was waiting to see if I would soften into something pliable.

Instead, I stayed steady.

“She’s beautiful,” I said.

“Yes,” Annie replied quietly.

We sat like that for fifteen minutes. No arguments. No explanations. No rewriting.

When Eleanor stirred, I handed her back.

“I’ll visit again,” I said calmly. “If the boundaries are respected.”

Annie nodded, but I could see she wasn’t used to this version of me. The one who didn’t negotiate herself away for access. The one who could hold love without surrendering dignity.

Henry called once after that.

I didn’t answer.

He didn’t call again.

Life continued, not dramatically, but firmly.

I became known at the community center as the woman who didn’t flinch. The one who could say, “No,” without apology and still sleep at night.

Janet and I took walks in the evenings. Michael came over for Sunday dinners. Eleanor grew, slowly, carefully, on my terms.

Annie and I did not return to what we were.

We built something else. Smaller. Clearer. Conditional on respect.

I learned something through all of it, something I wish someone had told me years ago.

You can love your child without financing their delusions.

You can adore your grandchild without surrendering your autonomy.

You can grieve the daughter you raised while protecting yourself from the woman she became.

And you can walk away from a table set to strip you down and still leave with everything that matters intact.

The greatest gift I gave my granddaughter was not money.

It was the example of a woman who could not be bullied out of her own life.