My Kids Lied to Exclude Me From Their Celebration, So I Showed Up Anyway

Mornings in Blue Springs always start the same way, and I’ve always found comfort in that.

The light comes first, thin and pale at the edges of the curtains, as if it’s testing whether I’m awake before it commits to the day. The house creaks in familiar places. The radiator coughs once like an old man clearing his throat. Somewhere outside, a bird insists on practicing the same three notes until it gets them right.

At seventy-eight, every morning feels borrowed.

Some days I wake up grateful and steady. Some days my joints ache so sharply that even sitting up is a negotiation, and the walk to the bathroom becomes a small victory I refuse to call what it is. I’ve learned not to dramatize pain. I’ve also learned not to deny it. You can do both at the same time, apparently, if you live long enough.

My little house on Maplewood Avenue isn’t what it used to be. Nothing is. The living-room wallpaper has faded in the exact places where the afternoon sun hits, a ghost of floral patterns softened by thirty years of seasons. The porch steps creak louder every spring. George always said he’d fix them. He said it the way men say they’ll do something someday, as if someday is a place you can actually reach if you keep driving.

He never got around to it before the heart attack took him.

Eight years have passed, and I still talk to him some mornings. Not in a tragic, theatrical way. Just in the way you talk when silence gets too big. I tell him the news as if he’s out back checking the bird feeder or fussing with the garden hose. I tell him when the neighbor’s cat has been sleeping on the porch again. I tell him when I can’t find the good scissors. I tell him when the aches are worse.

This is the house where Wesley and Thelma grew up, where their voices once bounced off the walls and off each other. Where the hallway still remembers their footfalls running late for school. Where the kitchen table remembers homework spread out like a battlefield. Everything in this house remembers their lives.

Now it’s so quiet it sometimes feels like those days never happened.

Thelma comes by once a month, always in a hurry, always glancing at her watch as if my kitchen is a waiting room. Wesley shows up more often, but only when he needs something. Money. A signature. Someone to absorb his urgency while he pretends it’s not desperation.

Every time he swears he’ll pay it back soon.

In fifteen years he has never paid back a dime.

I’ve made peace with a lot of things in my life. My children using me like a bank is not one of them, but peace is easier than war when you live alone and your heart gets tired.

Today is Wednesday, my pie day.

I bake blueberry pie not for myself, but for Reed, my grandson. The only one in this family who visits without an ulterior motive. The only one who doesn’t walk into my house with a list of needs before he even asks how I’m doing. He comes because he wants to sit. Because he likes my stories. Because he likes the quiet. Because he likes being here.

I hear the gate slam and know it’s him.

Reed has a particular walk, light but slightly clumsy, like he hasn’t fully settled into his tall frame. When he was little, he ran everywhere, arms pumping, a boy who believed the world would keep up with him. Now he moves like he’s thinking and walking at the same time, which is a sign of a mind that never quite rests.

“Grandmother Edith,” his voice calls from the doorway. “I smell a specialty pie.”

“You always do,” I say, and my smile comes easily for him. “Come on in.”

He leans down to hug me, careful of my shoulders the way he learned to be careful after I had a fall two winters ago. It’s an ordinary hug, not dramatic, not overly tender, just real. I have to tilt my head back to look at his face when we break apart.

When did he get so big?

“How’s school?” I ask, setting him at the kitchen table.

“Still wrestling with higher math,” he says, already reaching for his plate like the pie has been calling him by name. “But I got an A on my last exam. Professor Duval asked me to help on a research project.”

“I always knew you were smart,” I tell him as I pour tea. “Your grandfather would be proud.”

At the mention of George, Reed goes quiet for a moment. Not sad exactly. Thoughtful. His gaze slides toward the window where the old apple tree stands in the yard. George taught him to climb it when he was seven, scolding him gently about footing, standing underneath with his arms half-raised as if he could catch a falling child by will alone.

“Grandma,” Reed says suddenly, returning to his pie as if he needs the motion of eating to steady his thoughts. “Have you decided what you’re going to wear on Friday?”

“Friday?” I turn to him, puzzled. “What’s on Friday?”

Reed freezes with his fork halfway to his mouth. The pause is small, but something in it sharpens my attention, the way a silence sometimes does when it’s carrying something heavy.

“Dinner,” he says cautiously. “It’s Dad and Mom’s anniversary. Thirty years. They have reservations at Willow Creek. Didn’t Dad tell you?”

For a second, my brain tries to make it ordinary.

Thirty years. Of course they’d celebrate. Of course they’d go to Willow Creek with its linen tablecloths and polished wood and the kind of prices that make my stomach tighten.

But then the question arrives with it, quiet and unavoidable.

Why am I hearing this from my grandson and not my son?

I sit back slowly, tea cup warm against my fingers, and feel something cold slide through me.

“Maybe he was going to call,” I say lightly, because habit makes you protect your children’s image even when they don’t deserve it. “You know your father. Always putting things off.”

Reed picks at a crumb with his fork, eyes lowered. “I guess,” he says, but there’s no conviction behind it.

When Reed leaves, promising to stop by over the weekend, I stand at the kitchen window for a long time and stare out at the quiet street. Maplewood Avenue looks the same as it always does. Lawns trimmed. Mailboxes straight. People moving through their lives like nothing ever changes.

The phone rings and snaps me out of it.

Wesley’s number.

“Mom,” he says, and his voice sounds strained, like he’s already exhausted from the lie he’s about to tell. “It’s me.”

“Hello, darling,” I answer. “How are you?”

“I’m fine.” He clears his throat. “Listen, I’m calling about Friday. Cora and I were planning a little anniversary dinner, but we’re going to have to cancel. Cora caught a virus. Fever and all that. Doctor says she has to stay home.”

He says it quickly, like if he rushes through the words they won’t have time to become suspicious.

“Oh,” I say. “That’s too bad.”

Something about his tone makes my skin prickle. He’s performing. Not well, but he’s trying.

“Is there anything I can do?” I ask. “Bring chicken broth, maybe? Soup?”

“No,” Wesley says too fast. “No, no, we have everything. I just wanted you to know. We’ll reschedule.”

And then he hangs up before I can say anything else, as if he’s afraid of what my questions might uncover if the call lasts too long.

I stare at the phone in my hand, listening to the dead line.

The conversation leaves a strange aftertaste, like a sip of milk you suspect has turned.

That evening, I call Thelma casually. I keep my voice light, conversational, the way women do when they’re hunting truth without showing their teeth.

“How’s Cora?” I ask. “Wesley said she’s sick.”

“What?” Thelma sounds genuinely confused. “Sick?”

“Yes,” I say. “A virus. Fever.”

There’s a pause.

Thelma exhales, impatient now. “Mom, I have so much to do at the shop before the weekend. If you want to know about Cora, call Wesley.”

“But you’re coming to their anniversary on Friday, right?” I ask, still aiming for casual.

Silence.

Not the brief pause of someone thinking. The pause of someone trapped.

“Oh,” Thelma says finally. “That’s what you mean. Yeah, sure.”

Her tone shifts sharper. “Look, I really have to go.”

The line clicks dead, and I stand there in my quiet kitchen with the phone pressed to my ear, feeling something unpleasant settle in my chest.

They’re hiding something.

Both of them.

Thursday morning, I go to the supermarket. Not because I need much, but because the act of moving through the world keeps me from sitting too long with my thoughts. The produce section smells of oranges and green bananas. The floor is slicker than it should be, and I take careful steps.

That’s where I run into Doris Simmons.

Doris works at the flower shop with Thelma. She’s always had a voice that carries, and a face that tells you she knows more than she should.

“Edith!” she says brightly. “Well, look at you. Still upright and elegant.”

“Doris,” I reply. “Are you still working with Thelma?”

“Of course. Tomorrow is my day off, though.” She winks. “Thelma’s taking the evening off for a family celebration. Thirty years, can you believe it? That’s a big date.”

I feel my smile stiffen.

So dinner wasn’t canceled.

Wesley lied.

The phone rings later. Reed again.

“Grandma,” he says, voice apologetic, “I left my blue notebook at your place. Did you see it?”

“I’ll look,” I tell him, and I begin scanning the couch cushions.

While I look, Reed keeps talking, unaware he’s stepping deeper into it.

“If you find it, could you give it to Dad tomorrow?” he asks. “He’ll pick you up, right?”

My fingers freeze on a cushion.

“Pick me up?” I repeat.

“Well, yeah,” Reed says slowly, sensing the shift. “For dinner at Willow Creek. I have class until six, so I’ll meet you there. Dad said he’d pick you up.”

The room goes quiet in my ears, like someone has turned down the volume on the world.

“Reed,” I say gently, “Wesley told me dinner was canceled. Cora is sick.”

There’s silence on the other end. A long, uncomfortable silence.

“Grandma,” Reed says slowly, “I don’t understand. Dad called me an hour ago. He asked if I could be at the restaurant by seven. He said everyone’s coming.”

My legs feel weak. I lower myself onto the couch.

So that’s how it is.

I wasn’t invited.

Not forgotten. Not an accident. Not a misunderstanding.

Deliberately excluded, and lied to so I wouldn’t show up.

“Grandma?” Reed’s voice tightens with worry. “Are you okay?”

“Yes,” I lie, because old habits die hard. “I must have misunderstood.”

When we hang up, I sit in silence staring at the framed photograph on the mantle. George and I in the middle, the kids smiling on either side, Reed small and sunburned, grinning like the world was made for him.

When did I become someone best left out?

A burden.

An inconvenience.

Something you lie to because it’s easier than being honest.

I go to the closet where I keep documents. Not because I know what I’m looking for at first, but because my body needs motion and my mind needs something solid to hold. I pull out George’s will, the deed to the house, insurance papers. All the things my children have been circling for years with forced casualness.

Wesley has hinted more than once that I should sign the house over to him. Thelma has suggested I sell and move into Sunny Hills, as if it were a cute idea like switching brands of tea.

I’ve always refused, because something in me felt the shape of their hunger even when I didn’t want to admit it.

Now I see it more clearly.

The phone rings again that evening. Cora.

Her voice is bright, cheerful, entirely too energetic for someone who supposedly has a fever.

“Edith, honey,” she says sweetly, “how are you? Wesley told me he called you about Friday.”

“He did,” I say evenly. “He said you were sick and dinner was canceled.”

“That’s right,” Cora replies quickly. “Terrible virus. Knocked me right off my feet.”

“Poor thing,” I say, and let a pause stretch. “Say hello to the others for me.”

“The others?” Her voice tightens.

“Yes,” I say softly. “Thelma. Reed. Everyone who is still going, even though dinner is canceled.”

Another pause. A smaller one this time, the kind that tells you the person on the other end is scrambling.

“Oh yes,” Cora says too brightly. “They’re all so upset. But what can you do.”

I look out the window at the darkening sky.

Now I have confirmation.

They can’t even keep their story straight.

I hang up and stand in the quiet house, listening to the creaks, the settling wood, the old noises that once felt comforting and now feel like company I didn’t ask for.

Then I go to my bedroom closet and pull out the dark blue dress I haven’t worn since George’s funeral.

The fabric feels cool beneath my fingers. I slip it on slowly, carefully, and stare at myself in the mirror.

It still fits.

My hair is thinner than it used to be. My face more lined. But my eyes are the same eyes that raised two children and buried a husband and kept a home running when everything wanted to fall apart.

If Wesley and Thelma think they can quietly cut me out of their lives, they have forgotten who I am.

Edith Thornberry has never been a woman who disappears just because someone wishes she would.

Friday morning arrives under heavy clouds, the sky low and gray as if it has decided to mirror my mood.

Mrs. Fletcher walks her dachshund past my porch. She waves. I wave back, thinking about how few people are left who are genuinely happy to see me.

My phone rings again. Wesley.

This time his tone is suspiciously cheerful, the voice of a man making sure the door he locked is still locked.

“Mom,” he says, “good morning. How are you feeling?”

“Fine,” I answer. “How’s Cora? Better?”

There’s a pause, too small for anyone else to catch, but I catch it.

“No,” Wesley says quickly. “Same. Fever. Lying down.”

“That’s a shame,” I say. “I was thinking of baking her a chicken pot pie and bringing it over.”

“No!” Wesley says too fast, then tries to soften it. “No, you don’t have to. I’m just calling to see if you need anything.”

He’s checking.

Checking to see if I’m going out tonight.

I let my voice turn gentle. “Thanks, son. I’ve got everything. I’m going to spend the evening reading.”

“Oh,” Wesley says, relief leaking into his tone. “That’s a great idea.”

We hang up.

At five o’clock, I call for a ride.

When the driver asks the address and I say Willow Creek, he glances at me in the mirror.

“That place is… pricey.”

“I know the prices,” I reply calmly.

Willow Creek sits on the edge of town near the river, a red-brick building half-buried in greenery. The lights glow warmly through the windows as the sky darkens.

“Wait for me,” I tell the driver. “I won’t be long.”

I walk around the side toward the guest lot, and I see the cars immediately.

Wesley’s silver Lexus.

Thelma’s red Ford.

Reed’s old Honda.

They are all here.

All of them.

Except me, the person they lied to keep away.

The pain is so sharp it steals my breath for a moment. It isn’t just sadness. It’s recognition. It’s the clean understanding that this isn’t a misunderstanding. They chose this.

I walk slowly to the window and find a gap in the curtains.

There they are at a large round table. Wesley at the head. Cora beside him, healthy, laughing, her face glowing under chandelier light. Thelma. Reed with Audrey. A few others I don’t recognize. Champagne bottles catching light like jewels.

They’re laughing like nothing is wrong.

Like I’m already gone.

A tear slides down my cheek. I wipe it away with an irritated swipe.

Now is not the time for tears.

Now is the time for decisions.

And I turn from the window and walk toward the entrance.

The lobby doors opened with a hush like a secret being admitted.

Warmth wrapped around me immediately. Not comfort, exactly, but temperature and perfume and polished wood. Willow Creek always smelled like money spent without guilt. Butter. Wine. The sharp sweetness of cut flowers. A faint citrus cleaner underneath it all, as if luxury required constant wiping.

A young man in a crisp uniform stood at the host stand, shoulders straight, smile practiced.

“Good evening, ma’am. Do you have a reservation?”

“I’m here to see the Thornberry family,” I said. My voice surprised me with how steady it sounded. “Wesley Thornberry. I’m his mother. Edith Thornberry.”

Something changed in the young man’s posture. The smile became genuine, or at least more respectful. He looked me up and down, the dark blue dress, the pearl earrings I hadn’t worn in years, the way I held myself like I hadn’t come to beg.

“Oh. Mrs. Thornberry.” He stepped from behind the stand and dipped his head slightly. “Of course. Right this way.”

I followed him past the entryway where couples hung coats and murmured to each other. I could hear laughter deeper inside, the clink of glasses, a piano somewhere playing softly, the music so polite it barely existed. We reached the heavy double doors leading to the main dining hall, and the host paused as if giving me one last chance to turn back.

My heart beat hard. Not with fear, exactly. With that stubborn, rising heat that has lived inside me since I was a girl.

I had asked myself outside by the window if I should walk away with whatever dignity I had left.

But dignity isn’t always quiet. Sometimes dignity is showing up anyway.

“Mrs. Thornberry,” a voice said behind me.

I flinched, then turned.

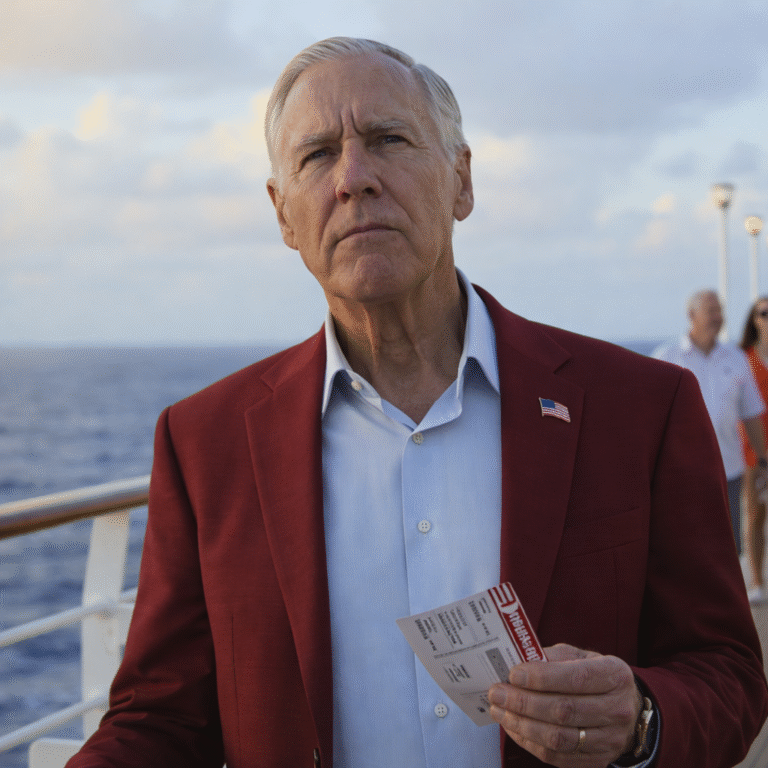

He stood there with the ease of someone who belonged in every room he entered. Tall. Mid-sixties. Gray beard trimmed neatly. A dark suit fitted perfectly. And on his lapel, a small gold pin shaped like a willow branch that caught the lobby light.

For a second my mind reached backward in time. A shy boy from down the street. A lanky teenager who borrowed books from my husband and ate my blueberry pie like it might disappear if he didn’t. A young man who used to say thank you as if he meant it with his whole body.

“Lewis,” I said, and my voice softened without permission. “Lewis Quinnland.”

His face lit with recognition that looked almost relieved. “Edith. I thought it was you.” He stepped closer, and his eyes took me in carefully, as if he were reading the years I’d lived since we last spoke properly. “You haven’t changed at all.”

I gave a small, tired laugh. “That isn’t true.”

He smiled. “Then you’ve changed in the best ways.”

Something warmed in my chest at that. Not romance. Not yet. Just the simple sensation of being seen.

“Are you here with your family?” Lewis asked. His gaze drifted past me toward the dining hall doors. “I heard Wesley was celebrating tonight.”

The word celebrating landed like a pebble in a pond, sending ripples of bitterness through me.

“I wasn’t invited,” I said quietly. It felt strange to say the words out loud, as if speaking them made them more real. “My son told me dinner was canceled. Said Cora was ill.”

Lewis’s expression tightened. Genuine indignation flashed across his features. “He told you that?”

“Yes.”

“And you found out otherwise?”

“My grandson slipped,” I said. “Not on purpose. He thought I knew.”

Lewis’s jaw worked once, like he was chewing on a thought he didn’t like. “That’s unacceptable.”

I watched him carefully, waiting for him to retreat into polite discomfort, the way people often do when family ugliness shows its teeth in public.

He didn’t.

Instead, he extended his hand, palm up, the gesture simple and sure.

“Let me escort you,” he said. “The mother of the guest of honor should not be standing in the hallway like a stranger.”

I hesitated. “Lewis, I don’t want to cause trouble for your restaurant.”

His eyes sharpened, not unkindly. “The only trouble here is disrespect. My restaurant is not a place where I allow that.”

His certainty steadied me. I took his hand.

His grip was warm and firm, not possessive, just grounding. It reminded me of George in a way I didn’t expect. Not because George and Lewis were alike, but because George had always held my hand when he wanted me to know I wasn’t alone.

Lewis glanced toward the doors. “How do you want to do this? Quietly? Or would you like me to announce you?”

“No announcements,” I said immediately. My pride had limits, and I didn’t want to give my children the excuse of embarrassment. “I want to walk in like I belong. No drama. Just presence.”

Lewis nodded once. “Elegance.”

He squeezed my hand lightly, then pushed open the doors.

The dining hall opened around us like a theater scene.

Chandelier light scattered across crystal glasses and silverware. White and cream roses stood in heavy vases, lilies and orchids arranged like someone had tried to buy beauty itself. The air carried butter and seafood and expensive wine.

And there, in the center, was their table.

A lavish centerpiece. A tiered cake waiting like a crown. A cluster of people dressed in their best clothes, laughing with the ease of those who believed the world was arranged properly.

Lewis led me toward them without hurrying, and with each step I felt the room’s attention shift. It wasn’t immediate. At first, people saw only Lewis. Then they saw who was beside him.

Reed noticed first.

His eyes widened, and his face drained of color. Audrey beside him turned pale and stiff. Thelma’s head snapped up, mouth parting slightly. Then Cora, then Wesley.

My son’s face went white in a way I had only seen once before, when he was a boy and George caught him in a lie he couldn’t wiggle out of.

For a long moment, Wesley just stared.

Lewis stopped at the edge of the table and spoke in a voice that carried without being loud.

“Mr. Thornberry,” he said pleasantly, with steel underneath, “I apologize for the intrusion. It seems your mother arrived a bit late. I took the liberty of escorting her to your table.”

Silence fell.

Not the soft silence of polite attention. The heavy silence of people realizing a lie has been cornered.

“Mom,” Wesley managed finally, and his voice sounded like it scraped his throat on the way out. “But… you said you’d stay home.”

“I changed my mind,” I replied calmly. “I decided I wanted to congratulate my son and daughter-in-law on thirty years of marriage.”

Lewis pulled out a chair between Reed and a middle-aged woman I didn’t recognize.

“Thank you, Lewis,” I said as I sat.

“Always at your service, Edith,” he replied with a slight bow. “I’ll have another appetizer brought out, and perhaps a bottle of our best champagne. On the house.”

He stepped away, leaving the table suspended in discomfort.

Wesley’s smile appeared, bright and strained, like a mask slapped on too quickly. “Mom, what a surprise. We thought you weren’t feeling well.”

“I feel fine,” I said, meeting his eyes. “And Cora seems to have recovered very quickly. This morning she had such a high fever.”

Cora’s cheeks flushed. She lowered her eyes to the tablecloth, fingers tightening on her napkin.

“Yeah,” she murmured. “I felt better by lunchtime.”

“Miraculous,” I said softly. “Especially since Doris Simmons saw you at the supermarket yesterday, perfectly healthy.”

Thelma set her glass down too sharply. It clinked against the table in a sound that cut through the tension.

“Mom,” Thelma said, voice tight, “maybe we shouldn’t do this here.”

“Do what, dear?” I asked. “Tell the truth?”

Her mouth snapped shut.

Reed leaned toward me, voice low. “Grandma, I didn’t know. I thought you knew.”

I reached over and squeezed his hand. His fingers were warm, steady. “I know, sweetheart. This isn’t your fault.”

Wesley coughed, the sound forced. “Well. Now that we’re all here, let’s just enjoy the night.”

He signaled a waiter with too much energy. The cake was cut. Plates distributed. Everyone moved like a troupe trying to resume the script after someone forgot their lines.

“What a beautiful cake,” I said, letting my gaze rest on the elaborate tiers. “Must have cost a fortune.”

“Oh, no,” Wesley said too quickly. “Not at all. It’s just a modest family party.”

I let my eyes drift slowly across the table. Across the seafood platter. Across the expensive wine bottles. Across the floral arrangements that could have fed a family for a week.

“Yes,” I said calmly. “Very modest.”

Wesley’s smile twitched.

“And how many guests?” I asked, glancing toward the strangers. “I thought you were having financial difficulties. Is that why you asked me for two thousand dollars last month? For car repairs?”

The middle-aged woman beside Reed stiffened. Someone at the far end of the table cleared their throat and stared into their glass.

Wesley’s jaw tightened. “Mom, can we not do this tonight? We can talk later.”

“Aren’t we talking now?” I asked. “Or am I still not supposed to be part of the conversation?”

Thelma leaned forward, trying to sound soothing and reasonable. “We thought it would be tiring for you. At your age.”

“At my age,” I repeated slowly, tasting the phrase. “It didn’t stop me from watching your cats last month while you went on a spa weekend. It didn’t stop me from helping Wesley with his tax returns. It didn’t stop me from lending him money.”

Thelma’s eyes flicked away.

Wesley’s voice tightened. “Mom, I wanted to invite you. I just didn’t think you’d be comfortable. You don’t like noisy gatherings.”

I stared at him.

“You don’t know what I like?” I asked quietly. “Who hosted Christmas dinner every year? Who organized the neighborhood barbecue every Fourth of July? Who planned your father’s birthday dinner even when he was in the hospital?”

Wesley opened his mouth, then closed it again. His eyes darted toward Cora as if she might rescue him.

She did not.

“Wesley,” I said softly, and the softness was more frightening than anger, “it isn’t my age. It isn’t noise. It’s that you didn’t want me here. You chose to lie instead of simply telling me the truth.”

The table went still.

Thelma’s face tightened into a grimace. “Mom, that’s not fair.”

“Fair?” I echoed. “Fair would have been honesty.”

Cora finally spoke, her voice clipped and defensive. “Edith, we were trying to protect you. You don’t need stress.”

Protect. The word stung with its false gentleness.

I turned my gaze toward her. “Did you protect me when Wesley told me you were sick and I spent all day worrying? Did you protect me when I sat alone in my kitchen thinking my son’s anniversary dinner was canceled because his wife was suffering?”

Cora’s throat worked. She looked at Wesley as if begging him to fix it.

Wesley’s smile collapsed into something weary and irritated. “Mom, please. Don’t make a scene.”

I set my fork down carefully.

“I didn’t come to make a scene,” I said. “I came to understand. When did my children become people who lie to my face? Who exclude me from their lives like I’m already gone?”

A long, uncomfortable pause.

From across the room, I saw Lewis moving discreetly between tables, his presence hovering like a quiet safeguard.

I took a breath and continued, voice controlled.

“You think I don’t notice things,” I said. “You think because I’m old I don’t see what you’re doing.”

Wesley stiffened. “What are you talking about?”

“The house,” I said.

The word landed and changed something in Wesley’s eyes. A flicker. Interest sharpened by fear.

Thelma’s fingers curled around her napkin.

“You’ve both been waiting,” I said calmly. “Waiting for me to either die or become helpless enough that you can decide my life for me. Sunny Hills. Realtors. Conversations I’m not included in.”

Thelma’s face flushed. “Mom, I was just curious about the market.”

“Curious enough to have a realtor walk through my home taking pictures while I was at the doctor,” I replied.

Dead silence.

Reed’s eyes widened. He looked from me to his parents with a dawning horror, as if he finally understood the stakes of what he’d overheard in fragments for years.

I reached into my purse and pulled out an envelope. Plain white. Nothing dramatic.

But the reaction at the table was immediate.

Wesley’s breath caught. Thelma’s lips parted slightly. Cora’s posture tightened, as if she’d been bracing for this without admitting it.

“You think I’m helpless,” I said quietly. “You think I’m too old to understand.”

I placed the envelope on the table.

“I’m not.”

Wesley’s voice came out thin. “Mom, what is that?”

I slid a single document out slowly, letting the paper speak before my voice did.

“I sold the house,” I said.

For a moment, no one moved.

Wesley stared at the paper as if it had turned into something living. Thelma made a small sound, half breath, half choke.

“What do you mean, sold it?” Wesley whispered.

“I mean exactly what I said,” I replied. “Three days ago. Mr. Jenkins handled it.”

“But… where will you live?” Thelma asked, and for a split second her voice sounded genuinely scared.

I studied her carefully. “Don’t worry about me. I rented an apartment near downtown. Near the library.”

Wesley’s face tightened. “An apartment? But the house is our family home. Dad wanted it in the family.”

“Your father wanted me safe and respected,” I said. “He wanted his children to be decent.”

I slid out the next document.

“The money from the sale,” I continued, “I donated to the city library. A new wing.”

The words didn’t land at first. They floated in the air as the table tried to understand them.

“You… gave it away?” Wesley said, disbelief sharpening into anger.

“Yes,” I said. “To name it after George. He loved books.”

Thelma’s eyes glistened. “That’s half a million dollars.”

“Yes.”

Wesley’s jaw clenched. “You’re punishing us.”

“I’m protecting myself,” I corrected gently. “And honoring your father.”

Then I pulled out the third document.

“And I updated my will,” I said.

Reed’s head snapped up, eyes wide.

Wesley leaned forward so fast his chair scraped. “Mom, don’t do this.”

“I already did,” I said.

I placed the will copy on the table and slid it toward them.

“Everything I have left,” I said, voice steady, “goes to Reed.”

Reed’s face crumpled. “Grandmother, no. I don’t want…”

“I know,” I said softly, meeting his eyes. “That’s why.”

A terrible silence filled the space between us.

Wesley’s face twisted with fury he could barely contain. Thelma looked stunned, then wounded, then angry in a way that felt more about loss than love.

Cora stared at the papers like they were a disease.

“You can’t do this,” Wesley said, and the tone was not sorrow. It was entitlement. “You can’t take everything away because of one misunderstanding.”

“One misunderstanding?” I repeated.

I leaned forward slightly.

“You lied to me,” I said. “You made me worry about illness that didn’t exist. You excluded me like I was a problem to manage. That isn’t one misunderstanding. That is a pattern.”

Thelma’s voice trembled. “Mom, we were worried.”

“Worry looks like care,” I said quietly. “Worry looks like calling. Showing up. Asking what I want. Not making plans about nursing homes and real estate behind my back.”

I stood slowly, gathering my purse. My knees protested, but I refused to show it.

“I won’t keep you from your celebration,” I said. “I came to understand what kind of family we are now.”

Wesley’s eyes flashed. “You’re leaving? Just like that?”

I looked at him, really looked at him, and saw not my little boy, but a grown man with a ledger where his heart should have been.

“I’m going home,” I said.

Reed started to rise. “I’ll walk you out.”

“No,” I said gently. “Stay. Finish your dinner, sweetheart.”

I turned toward Thelma and Wesley one last time.

“I still love you,” I said, because it was the truth and because I wanted them to feel it. “But love doesn’t mean surrendering your dignity.”

Then I walked away.

The room seemed to exhale behind me, whispers starting to rise as soon as my back was turned, the way people do when they’ve just watched something they weren’t expecting.

Lewis was waiting in the lobby, his expression soft but alert.

“Leaving, Edith?” he asked. “Not because of the food, I hope.”

“The service was excellent,” I replied. “I just needed to go.”

He nodded once, understanding more than I’d said. “Let me call you a car.”

While we waited, he studied my face carefully. “Tense atmosphere.”

“Family matters,” I said, and my voice came out tired.

“Sometimes the truth is bitter,” he said. “But necessary.”

A car pulled up. Lewis opened the door for me with an old-fashioned courtesy that made my throat tighten.

As I stepped in, he said quietly, “Edith, you deserve respect. You always have.”

I looked up at him, and for the first time that night, something in me softened.

“Thank you, Lewis,” I said.

He gave a small, sincere smile. “If you ever want tea, or company, my door is open.”

“I’ll remember that,” I promised.

The car pulled away.

I didn’t look back at Willow Creek.

I didn’t want to see whether my children followed me into the parking lot or stayed at the table whispering about what they’d just lost.

I already knew the answer.

The ride home was quiet in the way only late evenings can be.

The driver didn’t try to make conversation. He glanced at me once in the mirror, then kept his eyes on the road. I watched the lights of Blue Springs slide past the window, storefronts closing, sidewalks emptying, the town settling into its usual early sleep. It looked peaceful. It felt foreign.

For years I’d told myself that this town was my anchor, that the familiarity was what kept me steady after George died. But as the car turned toward my new apartment, I realized something I hadn’t allowed myself to admit yet.

The town hadn’t anchored me. I had anchored myself.

The apartment building was quiet when we arrived. Three stories, brick, modest but well kept. A small plaque near the door announced the name of the building in neat serif letters. I paid the driver, thanked him, and climbed the stairs slowly, my knees complaining but my mind clear.

Inside, the apartment smelled faintly of chamomile tea and old books. I’d been careful to make it feel like mine, not a substitute for the house on Maplewood Avenue. Different furniture. Different layout. Different habits. A place for the next chapter, not a shrine to the last one.

I set my purse down, slipped off my shoes, and stood for a moment in the living room, listening to the hum of the refrigerator and the distant sound of traffic. No shouting. No guilt. No waiting for someone else to decide when they had time for me.

I slept better that night than I had in years.

The days that followed were… strange.

Not painful in the dramatic sense. No sobbing fits. No wailing grief. Just a quiet recalibration, like a compass needle slowly settling into its true direction after years of being nudged off course.

On Monday morning, Wesley called.

I let it ring.

On Tuesday, Thelma called twice and left a voicemail.

“Mom,” her voice said, tight and careful, “I know things got out of hand the other night. We should talk. I don’t want this to be how things are between us.”

I didn’t delete it. I didn’t return it either.

On Wednesday, Cora sent a text.

Edith, I hope you’re feeling well. I’m sorry if there were misunderstandings on Friday. Family dynamics are complicated.

Complicated. The word people use when they don’t want to say we behaved badly.

I put my phone down and made myself a cup of tea.

Thursday was my first full volunteer shift at the library since the ceremony. The new wing was already buzzing with children, their voices echoing against fresh brick and glass. Bright rugs. Low shelves. Sunlight pouring through tall windows.

Miss Apprentice spotted me immediately.

“There she is,” she said, beaming. “Our benefactor.”

“Please don’t call me that,” I laughed. “I just wanted a place for children to love books.”

She squeezed my arm. “And you gave them one.”

I spent the morning helping a little boy find books about dinosaurs and reading aloud to a group of first graders who listened with the kind of seriousness only children can muster. When I finished, my throat was dry and my heart was full.

At lunch, Reed met me on the steps outside.

“Grandma,” he said, sitting beside me, “I wanted to check on you.”

“I’m all right, sweetheart.”

He hesitated, then asked the question I knew was coming.

“Are you angry at Dad and Aunt Thelma?”

I considered my answer carefully. “I’m disappointed,” I said finally. “And hurt. But anger… no. Anger takes too much energy.”

Reed nodded slowly. “They’re having a hard time.”

“I imagine they are,” I said gently. “Consequences can be uncomfortable.”

He smiled faintly. “You were incredible the other night.”

I chuckled. “I wasn’t trying to be.”

“You were,” he insisted. “You were… yourself.”

That, I realized, was the highest compliment he could have given me.

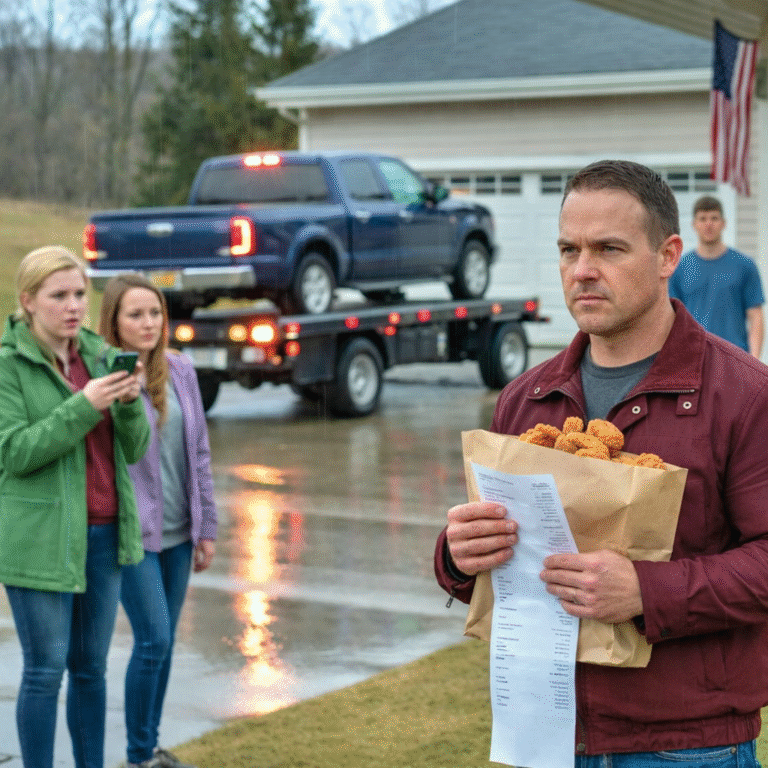

Two weeks later, Wesley showed up at my apartment.

I hadn’t told him my address. That told me everything I needed to know about how suddenly interested he’d become in my life.

I opened the door and found him standing there with a bouquet of lilies and an expression carefully arranged to look remorseful.

“Mom,” he said. “Can we talk?”

I studied him for a moment. My son. A man I loved fiercely, who had disappointed me just as fiercely in return.

“Yes,” I said. “We can talk.”

We sat at the small kitchen table. I poured tea. He didn’t touch it.

“I messed up,” Wesley began. “I should never have lied to you.”

“No,” I said calmly. “You shouldn’t have.”

He sighed. “We didn’t mean to hurt you. We just thought… you wouldn’t enjoy it. You always say you get tired.”

“I do get tired,” I agreed. “But that’s not the point.”

He shifted in his chair. “We’re worried about you, Mom. About the future.”

“I am seventy-eight,” I said evenly. “The future is shorter than it used to be. That doesn’t mean I don’t get a say in it.”

He winced. “Selling the house… donating the money… changing the will. That was extreme.”

“It was deliberate,” I corrected. “Extreme would have been pretending nothing was wrong.”

Wesley’s eyes flicked up. “So… there’s nothing left? No inheritance?”

I met his gaze without blinking. “There is. For Reed.”

His jaw tightened. “That’s not fair.”

“Fair?” I repeated softly. “Fair is not excluding your mother from your life and then expecting her to reward you for it.”

He rubbed his face with both hands. “Mom, I don’t want to lose you.”

I softened, just a little. “Then don’t treat me like I’m already gone.”

We talked for another hour. Not everything was resolved. It couldn’t be. Trust doesn’t rebuild in a single conversation.

But when he left, his hug was different. Less entitled. More careful.

That was something.

Thelma came next.

She didn’t bring flowers. She brought honesty.

“I was wrong,” she said, sitting across from me in the living room. “I got caught up in… planning. In assuming. I forgot you’re not just Mom. You’re Edith.”

That one landed.

“I don’t expect forgiveness overnight,” she continued. “But I want to do better. I want to show up.”

I nodded. “Then show up.”

She did.

Not perfectly. But consistently. Calls without an agenda. Visits without glancing at her watch. Small things that mattered more than grand apologies.

Life settled into a new rhythm.

Mornings at the library. Afternoons with books and tea. Evenings that were quiet but not lonely. Lewis and I went to the theater. Then to dinner. Then for walks where conversation flowed easily, without performance or expectation.

One evening, sitting on a bench beneath the oak near the library, he said, “You know, Edith, you’ve lived several lives already. You’re allowed to enjoy this one.”

I smiled. “I’m starting to believe that.”

Six months after that night at Willow Creek, I stood in front of the mirror adjusting a scarf before heading out.

My reflection looked different. Not younger. Just… lighter.

The phone rang.

Reed.

“Grandma,” he said brightly, “ready for our trip next month?”

“I think so,” I replied. “Where are we going again?”

“Anywhere you want,” he said. “That’s the point.”

I laughed, feeling something warm spread through me.

When I hung up, I looked around my apartment. At the books. The photos. The life I’d built in just a few months.

I thought about the woman who had stood outside a restaurant window, watching her family celebrate without her, heart breaking quietly.

That woman still lived inside me.

But she no longer lived alone.

I turned off the lights, locked the door, and stepped out into the evening.

Edith Thornberry was no longer waiting to be included.

She was living.